“Killing Kasztner: The Jew Who Dealt With Nazis,” a new documentary, portrays filmmaker Gaylen Ross’ attempt to understand why Reszo (Rudolf) Kasztner, a Hungarian Jewish leader who saved more than 1,600 people in war-time Budapest – more than Oskar Schindler – on the so-called Kasztner train, remains so controversial to this day.

In the course of the film, Ross tells several interrelated stories, including that of Kasztner’s rescue efforts during the Holocaust, as well as the stories of his life in Israel, his infamous libel trial (Kasztner was accused of collaborating with the Nazis) and his 1957 assassination by Ze’ev Eckstein, a right-wing Israeli nationalist. Finally the various threads are brought together as Kasztner’s daughter meets with her father’s murderer and Israel’s Yad Vashem acknowledges the importance of Kasztner’s rescue efforts, and accepts the Kasztner archive as part of its collection.

Kasztner has been faulted on many counts: for whom he saved and how he chose them (even though Kasztner personally chose very few of the train’s passengers, he did put his wife and 19 of his relatives on the train). For how he saved them – by negotiating with Eichmann and other German officials. And, finally, for not saving more people – 600,000 Hungarian Jews were murdered during that time, at one point as many as 12,000 a day – and although Kasztner had received Rudolf Vrba’s report on Auschwitz and the Nazi plans for the extermination of Hungarian Jewry, among the accusations made against Kasztner was that he did not sufficiently inform Hungarian Jewry of the report or its contents (a charge he disputed at his Israeli trial).

Kasztner is accused of allowing a few to live so that the others would go to their deaths without protest. As one of Kasztner’s daughters asks: “Why Kasztner? Why is Kasztner blamed for everything?”

The emotion Kasztner provokes to this day is striking. It’s as if those Jews who survived and those whose relatives were killed have displaced their anger at the Nazis and their own guilt feelings, both for surviving and for not saving others, onto Kasztner.

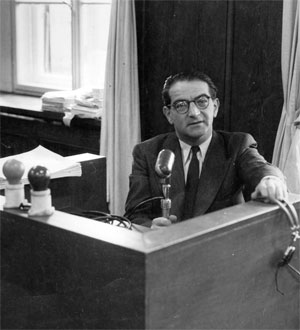

My father, Bruce Teicholz, knew Kasztner. They met in Budapest shortly after my father’s arrival there in early 1942 as a Polish refugee. Kasztner was co-head of the Hungarian Jewish Rescue Committee, my father was co-head of the Polish Jewish Rescue Committee, both of which helped refugees. When the Nazis arrived in Budapest, Joel Brand and Kasztner were the ones to negotiate with Eichmann. My father went underground, leading a group of forgers, couriers, smugglers and fighters who worked with Brand and his wife, Hansi.

My father, who died in 1993, defended Kasztner, believing, as the Supreme Court of Israel would come to conclude, that in impossible circumstances Kasztner did what he could and that lives were saved. “The thing you have to understand about Kasztner,” my father used to say, “is that he was a lawyer.” By which he meant that although Kasztner was never a practicing attorney, his instinct was to negotiate.

One of the arguments made by Merav Michaeli, Kasztner’s granddaughter, in “Killing Kasztner” is that “negotiating” doesn’t fit with how Israelis define their heroes – they prefer fighters or martyrs. Many of Kasztner’s critics argue that it is immoral to have negotiated with the Nazis at all, and that anything gained was done so at an unacceptable price – the lives of Jews.

Kasztner also symbolizes a rift in the Jewish psyche between resistance and accommodation, assimilation and defiance – and in Israel, between Ben-Gurion’s Labor Party and Menachem Begin’s Likud Party. Kasztner worked in a Labor post. The Defense at the trial sought to bring down the Ben-Gurion government, and Kasztner’s antagonist in his libel trial, attorney Shmuel Tamir, would eventually serve as Begin’s justice minister.

Many in Israel turned against Kasztner when it was revealed at trial that Kasztner gave affidavits in favor of SS officer Kurt Becher, commissar of all German concentration camps and chief of the economic office of the SS in Hungary – which spared Becher from being prosecuted at the Nuremberg War Crimes trials (Becher appeared as a witness). Kasztner also gave affidavits on behalf of Nazis Hermann Krumey and Dieter Wislency, whom he had negotiated with in Budapest. The Israel Supreme Court never reversed the lower court’s judgment about the “criminal and perjurious way” Kasztner saved Becher.

However, the film reveals that Israeli historian Shosanna Barri uncovered documents that indicate that the Jewish Agency not only knew of Kasztner’s dealings with Becher, but that its officials also were in dialogue with Becher themselves, hoping to gain Becher’s help in recovering Jewish property and in tracking Eichmann after the war’s end. This leaves open the question: Why didn’t Kasztner say anything about this? Was Kasztner covering for the Jewish Agency? Was he waiting for them to step forward and clear him? In the end, was Kasztner loyal to a fault?

Finally, Kasztner’s assassin, Eckstein, is an extremely compelling character. If you’ve ever wondered how terrorist organizations recruit assassins or suicide bombers; if you’ve ever wondered how an educated young person from a good family can be convinced that he needs to take on such a mission – watch this film.

Eckstein explains that his brain was “poisoned” by right-wing extremists who wanted to purge Israel of its corrupt elements, beginning with Kasztner. He says that today he bears no connection to the young man who committed those acts, but he nonetheless accepts full responsibility for his actions. In the film, a meeting between Kasztner’s daughter and his assassin is arranged at the daughter’s request (the assassin at first refuses, then relents). The meeting, albeit dramatic, is neither cathartic nor revelatory, but does seem to offer Kasztner’s daughter a measure of comfort, if not closure.

In light of all this and in spite of all this, the question remains: Why Kasztner? Why was he such a lightning rod?

To understand Kasztner you have to consider the human dimension and consider the man: imagine a person from Cluj, a Transylvanian border city, who arrives in Budapest and appoints himself as the representative of the Jewish people – that takes a certain chutzpah, a certain ego. There is something about Hungarian Jews of that era, in general, and in particular those worldly, assimilated Hungarian Jews who arrived in Budapest as lawyers and journalists (many of whom became playwrights or screenwriters and ended up in Hollywood). They seemed to think of themselves as magicians – charming, entertaining, able to pull a rabbit out of a hat.

Kasztner believed time was on his side – that if Eichmann could be stalled, the war would end.

Was Kasztner arrogant? Was he resented? Was he damned for what he did? And damned for what he couldn’t do?

Imagine being a Jew in a room with Eichmann, or riding in an SS staff car with Becher as Jews were being murdered daily; it is as horrifying as it is daunting to contemplate. Lives were in the balance and, thanks to Kasztner, lives were saved – not only those on the Kasztner train, but those that Becher spared in the concentration camps and those my father helped to get false papers or cross the border to safety.

Eichmann and the Third Reich had their own larcenous and murderous ambitions. But did Eichmann and Becher know the war was coming to an end? Did they fear war crimes prosecution? Did Becher give information to the Jewish Agency about “the Becher deposits,” confiscated Jewish fortunes in return for Kasztner’s affidavit? Nothing happened in a vacuum.

It is a human impulse to second-guess, to judge, to write history as a moral lesson, with right and wrong, winners and losers, heroes and traitors. But history is made by complex characters. We may never know the full truth animating the motives, agendas and politics of Kasztner or his many antagonists. But “Killing Kasztner” makes the case that history is a narrative in flux that can be rewritten as our own understanding of events deepen, and that Reszo Kasztner, in all his complexity, deserves to be remembered.