April 16, 2021

By Tom Teicholz

Amy Sherald’s new work, on exhibit at Hauser Wirth Los Angeles until June 6, 2021 (her first West Coast solo show) is a pleasure, a wonder, a breath of fresh air, a corrective, a display of mastery, brilliance, and soulfulness. It is about America, about the dignity of regular people, about being present and being seen, about painting, and about color (in every sense of the word).

The show consists of five paintings Sherald completed during the Covid quarantine. In some respects – as to overall feel, the colors and some of the subjects— it is a continuation of the work Sherald showed at Hauser and Wirth in New York in 2019 (reviewed here as “Sometimes the King is a Woman”). However, in other more important ways, these canvases represent a deepening of her work.

Although Sherald often uses real people whom she photographs as models for the figures in her work, she recasts them and their surroundings. Like a frame from a Hitchcock movie where meaning can be read into each detail, Sherald constructs her images in ways that ask us to take nothing for granted. Sherald paints, to quote the press materials for this show, “‘the things I want to see’ by depicting Black Americans in scenes of leisure and centered in stillness.”

As American as apple pie by Amy Sherald 2020 AMY SHERALD © AMY SHERALD COURTESY THE ARTIST AND HAUSER & WIRTH PHOTO: JOSEPH HYDE

In “As American as Apple Pie” (Sherald’s names her paintings after completing them, finding inspiration for titles in aphorisms, poems and written texts), one of the show’s larger canvases, a couple stands in front of a house. Everything in this painting says “All American”: The man is leaning against a car (of which we only see the rear half but recognize as an American car) dressed in a blue jean jacket, white T-shirt, khakis and white sneakers. The woman is wearing a pink T-shirt that says “Barbie.” She is carrying a pink flamingo purse – which matches her pink skirt, and pink shoes while her yellow-framed eyeglasses and gold hoop earrings match the house behind her. Behind them is a white picket fence, a green hedge and a yellow house with open white shutters. There is a crispness to the hard edges of the blocks of color – the jacket, the T-shirt, the house, that make the colors pop while the facial details recede into a more quiet zone. The sky is blue and there is something to the image that suggests we are in a town that is perhaps also a summer resort.

Sherald’s paintings are always hung low, at eye level, so the figures in her paintings often seem to be looking directly at you. Subtly, this adds presence to the figures who own the space in which they stand, naturally and organically.

In “A Midsummer Afternoon Dream” a woman in a blue dress and a yellow sun visor stands on the grass in front of a bicycle with a front basket in which there is a bouquet of daisies. Behind her is a white picket fence and behind it green stalks with daisies. A breeze is blowing her dress against her.

This image most brings to mind Sherald’s portrait of Michelle Obama and Sherald’s more recent portrait of Breonna Taylor for the cover of Vanity Fair magazine. Without in any way diminishing how great a painting the Michelle Obama portrait is and how important that painting has become for all who see it, I believe that “A Midsummer Afternoon Dream,” is indicative of the continued growth and expansiveness of Sherald’s technique as a painter. The Obama portrait was by design about the First Lady – and the flatness to the painting made Obama seem approachable yet regal. But in “Dream” the painting is so varied and detailed: The sneakers all finely rendered, The dress contains folds, giving a certain depth and dimensionality not present in the First Lady’s portrait, while the white picket fence and those daisies both gathered and wild speak eloquently about this moment, this woman, this dream. She stands like a windswept heroine of a Victorian romantic novel (or perhaps from Bridgerton!) transported to the present.

The exhibition features two striking individual portraits, one of a young woman, the other a young man. In “Hope is the thing with feathers (The Little Bird)” a young woman is wearing a dress that has a white bird in flight against a red background as its graphic adornment. The white bird recalls Picasso’s ‘Dove’ and the painting’s title is from Emily Dickinson. She stands before a baby blue background and I imagine that both dress and title are clues to her interior life that is hopeful, unformed yet in the process of formation. This is a painting about youthful idealism, about hopes and dreams.

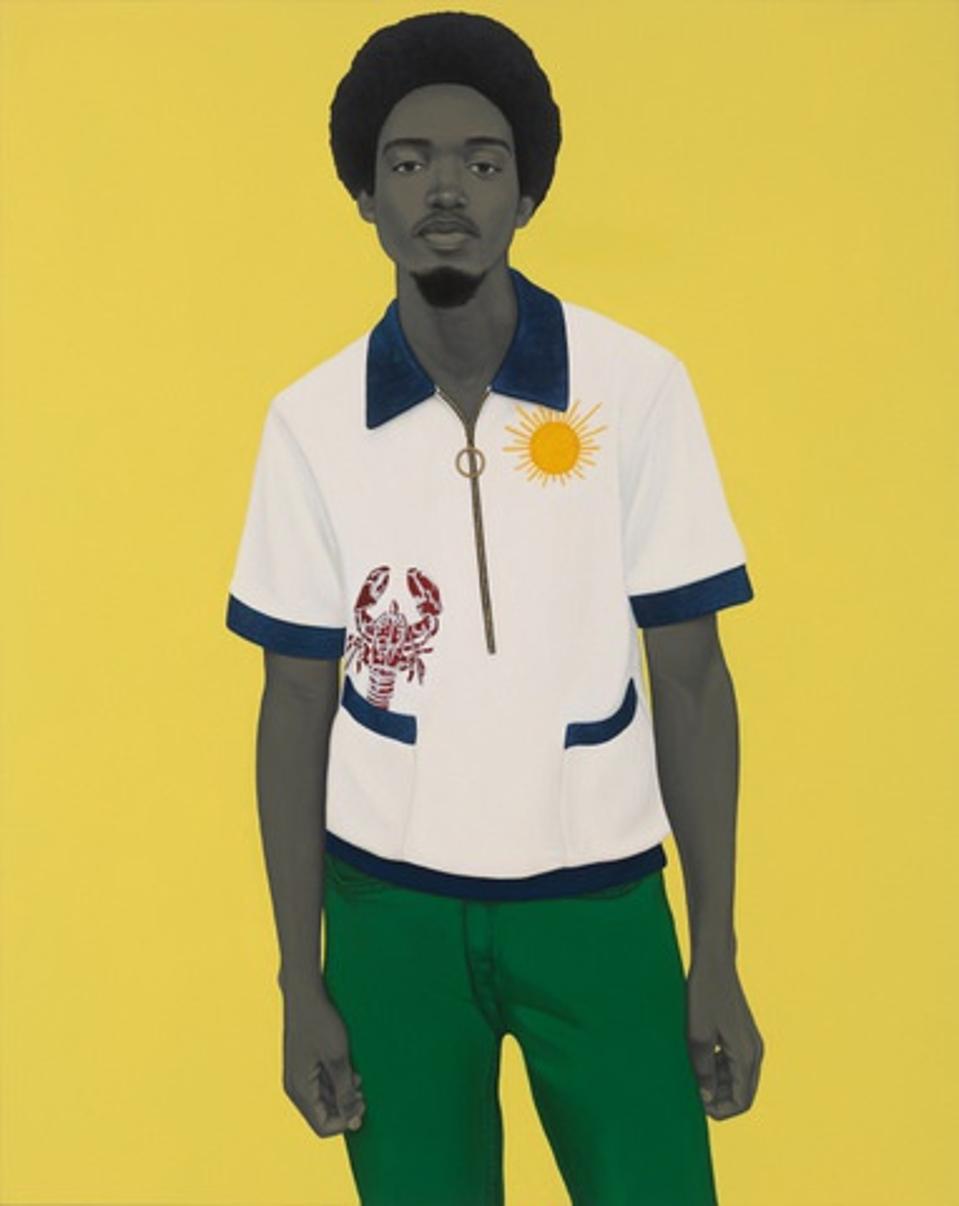

A bucket full of treasures (Papa gave me sunshine to put in my pockets…) by Amy Sherald 2020 AMY SHERALD © AMY SHERALD COURTESY THE ARTIST AND HAUSER & WIRTH PHOTO: JOSEPH HYDE

By contrast, Sherald’s “A Bucket full of treasures (Papa gave me sunshine to put in my pockets…)” presents a young man who is fully present. He is wearing a distinctive cabana shirt with a graphic of a lobster coming out of one pocket and a sun burst near his shoulder. He stands, cool, hip, self-assured, commanding his space. He needs no outside validation – and he is game, ready to engage.

My favorite painting in the show is “An Ocean away,” which like some of Sherald’s earlier paintings is set on a beach, yet unlike those images is not as carefree. There are two figures on the beach: A young man standing in a wetsuit holding a surf board, and an older man also in a wetsuit sitting on a different surfboard. The young man is gazing directly at us, and the older man is looking away. Sherald does not tell us what the man is looking at, or thinking about, but perhaps, as the title indicates he is looking out at the Ocean.

An Ocean Away by Amy Sherald 2020 AMY SHERALD © AMY SHERALD COURTESY THE ARTIST AND HAUSER & WIRTH PHOTO: JOSEPH HYDE

The boy is not fully confident, and there is in the painting tension between that which is rendered in hard edges and the softness and undefined nature of the sand. There is a red flag on the beach that the wind is making wave in reverse, away from the water. The Red flag means the ocean is dangerous and explains perhaps why the surfers are beached there.

To me, surfing speaks to a certain amount of status, class, privilege and leisure. However, perhaps being prevented by the red flag from enjoying doing so, causes the older of the two to ponder that they are, literally and metaphorically, “an Ocean away,” from the shores of West Africa from which, some 400 years ago, indigenous natives were captured, and taken to be sold as slaves in the New World.

That interpretation is solely my own. All the figures in Sherald’s work are Black which would be unremarkable if the appearance of Black figures in portraiture and art history were unremarkable. But it is not, and so Sherald’s work is, in part, not so much a corrective as way of opening our eyes (and that of art history’s) to the images, subjects, and persons who have always been there – if not represented often enough.

In this regard, Sherald is no more painting Black people than other painters were painting white people. She is painting the people she sees, much the same way as Alex Katz was painting the persons he came across. In fact, to render Black skin tones, Sherald uses grisaille, a method of using gray monochromes, historically used to render or imitate sculpture.

My point, however clumsily made, is that Sherald is not make paintings about Blackness or Black history so much as she is capturing those normal moments that are in no way race-based; in which Black people exist but in which they are rarely seen as present.

If, as Anna Julia Cooper, a 19th Century Black writer, activist and educator, wrote “Black Americans are ‘the great American fact,” then Sherald in her paintings is just stating facts.

As Ta Nehisi Coates has written, “Our notion of what constitutes “white” and what constitutes “black” is a product of social context.” In her paintings Sherald provides the social context for moments of Black joy and quietude. paintings about being seen that insist we look.