Ed Ruscha’s career retrospective at LACMA, ED RUSCHA / NOW THEN (first mounted at New York’s Museum of Modern Art) makes a strong case for the power of Ruscha’s hard-edged, minimalist, yet graphically strong works, as well as his many obsessive photo series, all of which have come to represent Los Angeles.

Ruscha, who is 86, was present at the press preview for the exhibition, in conversation with LACMA’s impresario Michael Govan. Govan was bubbling with pleasure about the artist and the exhibition, while Ruscha was just wry, laconic, and in good humor.

Ruscha was born in Omaha, Nebraska, but grew up in Oklahoma. At 18, he drove from Oklahoma City to Los Angeles to attend Chouinard Art School, which was a school for commercial art (it was later absorbed into CalArts).

Those qualities we attribute to Okies and the Mid-West, of a certain plain-spoken humility, together with a dry sense of humor (irony almost), remain evident in Ruscha to this day. Similarly, Ruscha’s Chouinard training in graphic design continues to inform his work. Facile perhaps, but true, nonetheless.

The LACMA show offers a unique opportunity to see the progression of Ruscha’s work along with some of his artistic side adventures. For example, one sees how Ruscha’s early work emerged from Pop Art (After graduating Chouinard, Ruscha had a studio above the Ferus gallery where he saw the first LA exhibition of Warhol’s Soup Cans). We see a glimmer of Warhol as well as Roy Lichtenstein in his appropriation of the graphics of the “Annie” typeface, as well as words such as “OOF” in his early works.

Ruscha’s humor is already evident in these works, and we see it even more as he finds ways to inject energy and drama into images, such as his Actual Size from 1962, which renders the word SPAM logo-like and beneath it depicts a can of spam that seems to be hurtling across the canvas with a smudge-like rocket trail behind it.

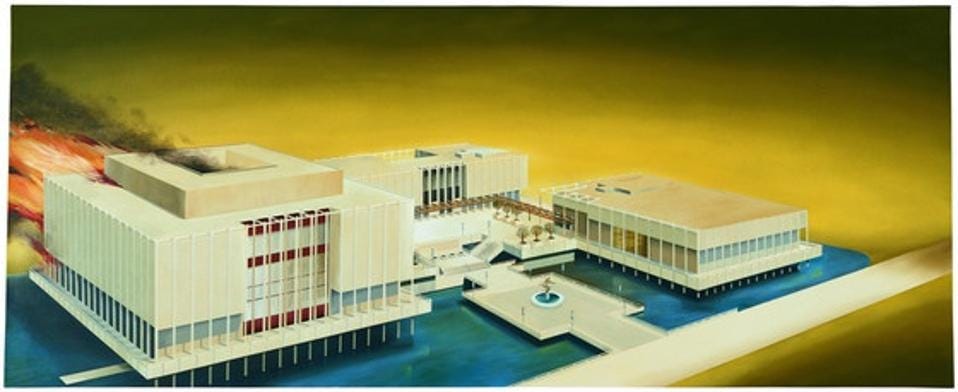

The exhibition also showcases how Ruscha found a distinctive horizontal visual perspective to render signs and images be it the “20th Century Fox” logo, the Hollywood sign, and a Standard Oil gas station sign. In search of unique perspectives Ruscha flew in a helicopter over Los Angeles, informing his work, Santa Monica, Melrose, Beverly, La Brea, Fairfax (1998); and his LACMA on Fire, which is being shown at LACMA for the first time.

Also featured are several of Ruscha’s photo projects, such as Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966) (for which Ruscha mounted a camera on the back of a flat bed and drove the length of Sunset Blvd, 26 Gasoline Stations, 34 Parking Lots in Los Angeles (which he shot from a helicopter), Some Los Angeles Apartments, and Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass. These photo projects are both prosaic and obsessive – and yet we can see not only how important they are to Ruscha but how they fed his unique takes on Los Angeles. In this way, Ruscha both documented an LA that has largely disappeared, and made it his own.

Over the course of his career Ruscha has had, by his own admission, “a romance with liquids,” and has incorporated honey, maple syrup, blood, Pepto Bismol, Pacific Ocean water into his works, at times using them to stain his canvases.

At the same time, Ruscha has explored the use of unconventional materials, perhaps the most famous example of which is Ruscha’s “Chocolate Room,” recreated for the LACMA exhibition. Ruscha soaked sheets in chocolate and used them to fashion a room, that when you stand in, smells chocolate.

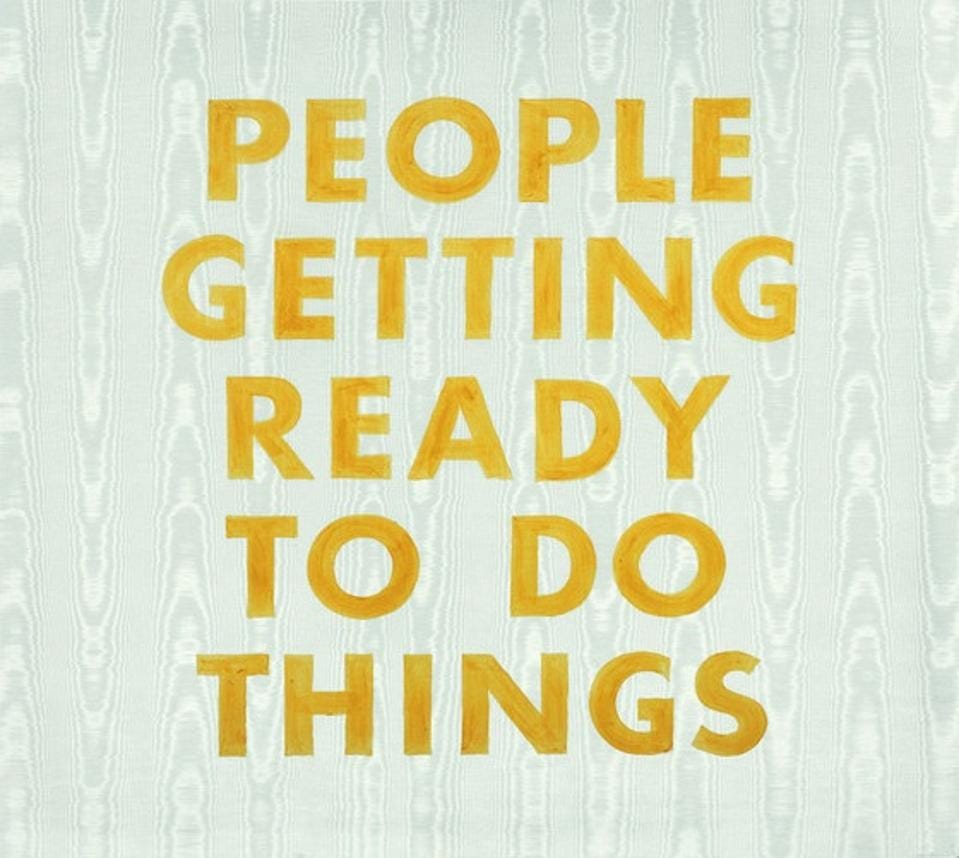

Ruscha is best known for his gnomic use of words and phrases in his art. What I find so interesting about these works is how they invite the viewer to find meaning where there may be none. It is the way the viewer makes associations to the words depicted that gives the work its power, and its appeal. In this way, Ruscha partners with the viewer in the artwork.

Certainly, text being part of artworks can be traced back to medieval art, and is a feature of much Islamic Art. Even in the notebooks of Leonardo, his handwriting, even in reverse, adds to the power of the work. In the present, it is interesting to note that following Pop Art, several artists such as Jenny Holzer, Barbara Kruger and Ruscha turned to the poetry of random (and not random) words for their Art. Perhaps this grew out of Poster-making and anti-Vietnam War Protests, or from a time when the written word was driving the culture.

At the same time, it is easy to dismiss Ruscha’s work as graphically satisfying and all surface pleasure; and his words as having the shallowness often attributed to Los Angeles and to Hollywood. However, like the works of David Hockney, which were often judged as too decorative or more concerned with gimmicks, like Los Angeles itself, the accumulation of work over time reveals the substance and deep artistry that have made Los Angeles the creative capital of the world. In a sense Ruscha’s work tells us that it is the prosaic in Los Angeles that is heroic and that makes the city a work of art.

The LACMA exhibition stresses the major elements of Ruscha’s work, the calm, the cool, the fun — all of which combine to resist interpretation and to make us believe that what you see is what you get. Yet what you also see is something deeper, something more fatalistic, something that is disappearing even as it is there right in front of us.