In the waning hours before coronavirus shut down New York, I visited a more-empty-than-usual Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

The Museum re-opened last October after several months of closure for expansion, renovation, and re-installation of the collection. Let me cut to the chase here: I love what the Museum has done

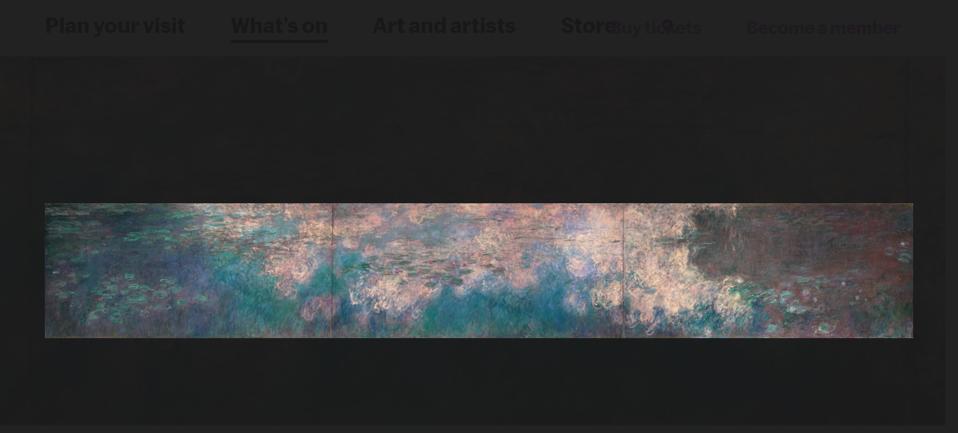

MoMA has found a way to return to the spirit of early curators Alfred Barr and William Rubin’s embrace of Modern Art as a story, and found a way to free that narrative to be more inclusive, diverse and less of a patriarchal collection driven by the male gaze. All the greatest hits and visitor favorites are on display. There’s Van Gogh’s “Starry Night.” There’s “Monet’s Water Lilies.” There’s Picasso’s “Demoiselles D’Avignon.” There’s Wyeth’s ‘Christina’s World.” And there’s Jackson Pollock. They are surrounded by works of artists who should always have been part of the conversation from Berenice Abbott to Eva Zeisel (and including Faith Ringold, Frida Kahlo and Natalia Gonchorova). There is a flow to the rooms and the floors now, and they have also paid attention to creating views and vantage points to view the museum itself—the stairs going up and down, the garden from above and other. It all feels just right. Finally. Again.

It’s no secret that I wasn’t fan of MoMA’s previous expansion and the choices they made in displaying their permanent collection and how they reorganized the garden. The last time I visited MoMA, it was a nightmare: the entry lobby was as crowded as Grand Central Station, the permanent collection was installed in a manner that lacked coherence, and you moved through the museum as if through a department store. Moreover, the garden was arrayed in a way that was not prone to contemplation. I searched the garden for Rodin’s Balzac, once the anchor of the sculpture garden—but it was not there. A staff member inside informed me that the sculpture had been rotated out of service and she couldn’t say when it would return.

I am happy to report that Balzac is back. He stands in the North West corner like a sentinel looking out over the garden, which itself is more open and less congested and feels, again, like an inviting public space, as it was always meant to be.

Another change (or corrective if you will) also pleases me greatly. They have hung the paintings lower at or beneath eye level and dispensed with old or ornate frames. The effect is to make the paintings more inviting, more approachable, less like an out of reach cultural totem.

The permanent collection proceeds chronologically for the most part, but also thematically, or with a certain curatorial grouping here and then. Painting, Photography and Sculpture or no longer separate but part of the flow of MoMA’s didactic presentation. They have also created moments within that narrative for the art to be in conversation with itself over time. One example of this is their ‘Artist’s Choice’ program that has one artist, current Amy Sillman, curate a room from the collection and juxtapose works in ways that challenge and engage the viewer. The total effect of MoMA’s reinstallation is to return the thrill of discovery to seeing the collection again. At the same time, given that this is no longer just a greatest hits collection and there are so many works to see, they have designed the rooms and the spaces surrounding them with attention to allowing visitors places to sit and contemplate the art. That is a luxury that has been missing for some time at MoMA.

MoMA since its inception erred on the side of believing that art history developed as a recognizable progression from one artistic movement and style to another. Impressionism was followed by Cubism, Fauvism, Futurism, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, Minimalism, and so on and so forth. Recent art critical thought and curatorial practice has exploded this notion of art history as antiquated. Recently Yale University canceled a popular art history survey course for a number of reasons. The course focused on artworks that were considered as too predominantly male, and not diverse. The course was criticized because it hewed to these very rigid notions about what makes art worthy of being including in its history. They are right about all that.

But great art does speak to us. Important artworks do tell us a story – about the painters, about questions and concerns posed and/or addressed in their work (some of them artistic, some of them cultural, some of them even political) and about the artists and their times. However, the story they tell should be not be limited to white male artists or only devoted to the male gaze – there is a larger, more inclusive story that has always been there – it just hasn’t always been told.

All of which is to say that MoMA has recommitted to telling the story of Art as it was made, historically, in a way that broadens our knowledge, challenge us and that continues to life our spirits.

Welcome to the new MoMA—which is like the old MoMA in all the right ways, improved and enlarged not only in its physical space but in its breadth of vision.

MoMA is now closed for the safety of its employees and its visitors. It will be there in all its renewed splendor when we are allowed to social again. In the meantime, MoMA on its website is offering tons of free classes, home art projects for families, resources for teaching and learning about art online, and they are promoting #museumathome for more activities. They also have 84,000 artworks viewable online. Even from home one can enjoy MoMA at its best.