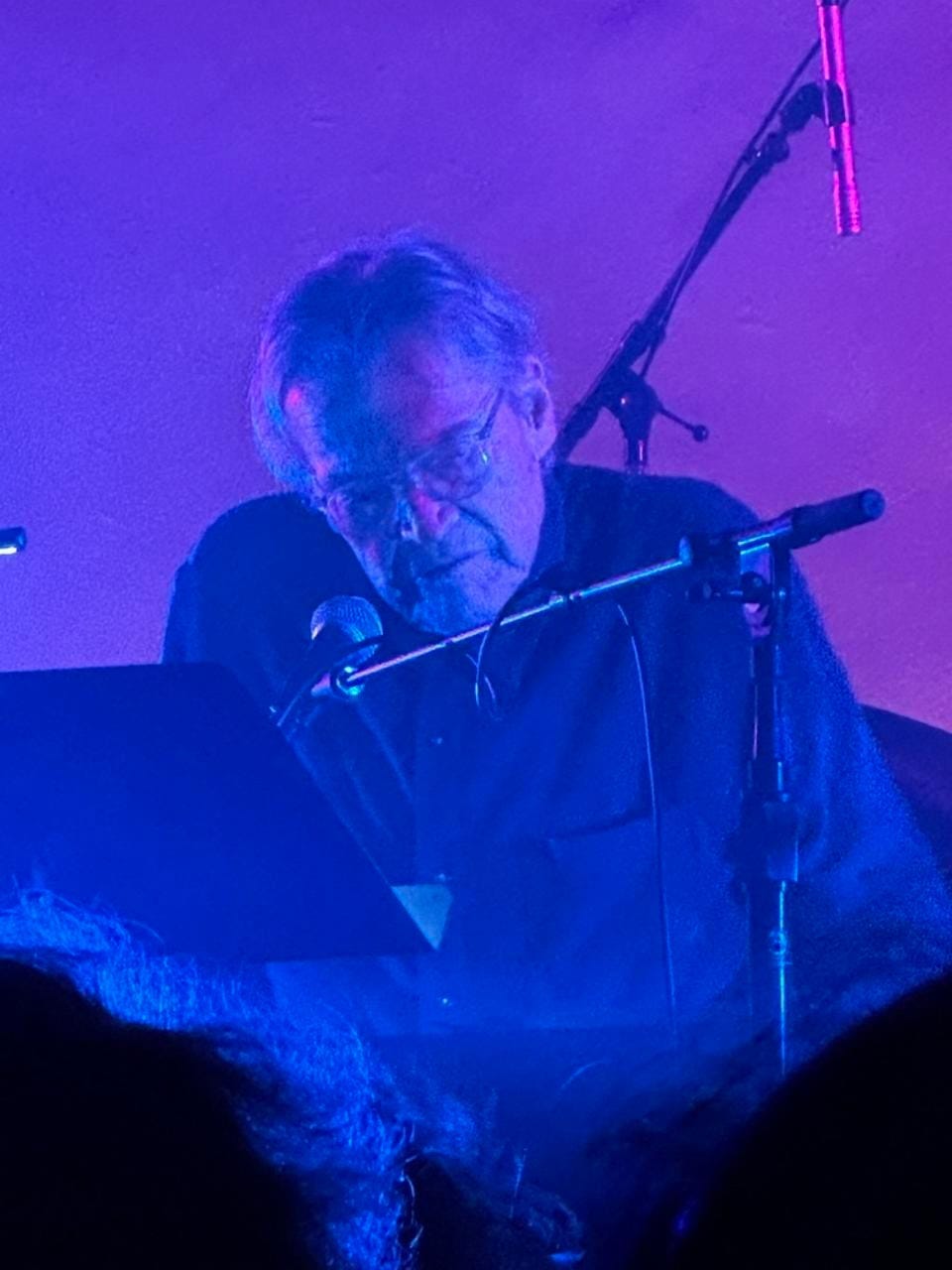

There must be something in the water in Lubbock, Texas, that produced songwriters, musicians and artists such as Buddy Holly, Mac Davis, and the singer-songwriter and visual artist Terry Allen, whose artwork was featured at LA Louver’s booth at Frieze LA and who gave two performances during Frieze Week at the Masonic Lodge at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery.

Allen performed with his band, The Panhandle Mystery Band, which featured not only his son, but also Charlie Sexton (who I’ve seen backing Bob Dylan, and who Allen says he’s known since Sexton was 12 years old). His wife Jo Harvey Allen also read at the event, which was a great night, filled with poetry, funny stories, great songs, and great music.

There was one particularly comic story about a waitress they met at the Denny’s on Sunset in Hollywood; and how several years later they were at a circus in Lubbock when they saw a freak show performance by a woman who sprouted hair and became the Gorilla Girl who, after the show, turned out to the same woman from Denny’s who told them “She liked waitressing but she was made for the carnival life.”

When I asked Allen about Lubbock, he explained that, for him, as for others, Lubbock was the kind of place that you were in a hurry to leave behind.

In Lubbock, Allen recalled seeing Buddy Holly performing on Friday nights at the local roller rink there, and the fights that ensued. Seeing Elvis perform in Lubbock before an audience of not more than 100. Allen recalls that the first time he saw Elvis, “He opened for Little Jimmy Dickens” (Dickens being the person for whom Hank Williams wrote Hey Good Looking so Dickens could have a hit). Allen recalled that Elvis had just released Milkcow Blues Boogie. “That w0as his first single on Sun [Records]. And then wasn’t but a short time later that Heartbreak Hotel came out and the whole town was there.”

In Lubbock you were driving before you had a license, but once you did, you were out of there. The goal was, as Mac Davis put it, to have “Texas in the rear-view mirror.”

As for his own musical inspiration, Allen recalled, “The most moving thing to me was the first time I heard Bo Diddley.” Allen would listen to late-night radio stations such as KOMA out of Oklahoma City. Which broadcast his. “biggest influence”: DJ Wolfman Jack.

As Allen shared during the narrative part of his performances, he was drawing from an early age. Allen told me, “I remember my dad was usually the one that woke me up to go to school. I usually hated to go to school, but what made me get up and go, was thinking about having a pencil and what it felt like to move it on paper, and that feeling was always kind of a comfort to me. And I think that played into it.”

Lubbock was not a place with a lot of Art to get inspired by. Instead, as Allen recounted, his earliest inspiration were his uncles, whose bodies were covered in tattoos. For Allen growing up “the real artists that were very influential were comic book artists and tattoo artists.”

Allen’s father, “Sled” Allen, had been a catcher for the St. Louis Browns baseball team and became “a sports promoter and kind of local entrepreneur who brought in dances.” Allen explained that in Lubbock, he held dances on Friday nights that were held for a Black audience. Saturday night was a Country night for white audiences. Wednesdays were wrestling matches.

“I grew up working there from the time I was about six years old. And you saw the posters for all those [concerts and wrestling matches]. I can remember going in the bathrooms and seeing these elaborate porno drawings that people did on the walls of the stalls… And I always had that idea of that music you could hear in the background. And these bizarre images.”

If music was not going to be his ticket out of Texas, then Art would be. Allen spent one semester at Texas Tech where he had a drawing class he really liked. The teacher had attended Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles (which was later absorbed by CalArts), and so Allen and a friend applied and were accepted.

Turning up in LA from Texas in the early 1960s was, Allen recalled, “like going to Mars… I remember we drove straight through to LA, straight to the beach, got out of the car, walked across the sand into the water, and it was that’s the fastest way we could get from Lubbock. It was coming to another world, a huge change in my life.”

“The Sixties were an amazing time to be in LA…. Everything was changing and merging, and LA was very exciting at that time.” Allen recalls seeing Andy Warhol’s multi-media happening, The Plastic Inevitable, which featured The Velvet Underground performing with Nico, and was one of the first performances with a light show, that set the stage for the rock performances to follow. And then Warhol had his show at Ferus Gallery.

Allen and some fellow artists decided to start their own coop gallery called Gallery 66 on Western Avenue, inspired to do so by Walter Hopps, who Allen called, “our bastard saint.” Allen recalled that they would hold an exhibition and invite Hopps, who wouldn’t show. But then Hopps would call at 3AM and say, “I’ll meet you there in 30 minutes.” Allen would then call all the artists and they would all show up and Hopps, as Allen recalled “He would come in literally in the back door with the trench coat, come in and walk around, look at all the work, and said, ‘all of you can do better than this’ and leave, and that was pretty much always his review.”

Allen’s own first show of his work was held in Pasadena. He had a little corner, and he was next to a show of work by Joseph Cornell, and Dennis Hopper who had a show of his photographs.

So, it was a nice start.”

By the end of the decade, in 1970, Allen left LA and moved back to Lubbock for five months “to kinda regroup,” when he was invited to teach art Berkeley. They moved to the Bay Area, where he taught for two semesters after which he was offered a position at Fresno, “which I jumped on because we had two little kids and no money.”

“It saved us,” Allen now says, adding, “I always thought of teaching as like falling into a hole with a little money in the bottom.”

“I taught there for like seven years and, but we lived there for 17,” Allen said, “because our kids were raised there. And it was last vestige of where your kid could get on a bicycle in the morning and ride it to school and come back and you didn’t have to worry about [him] getting shot in the street.”

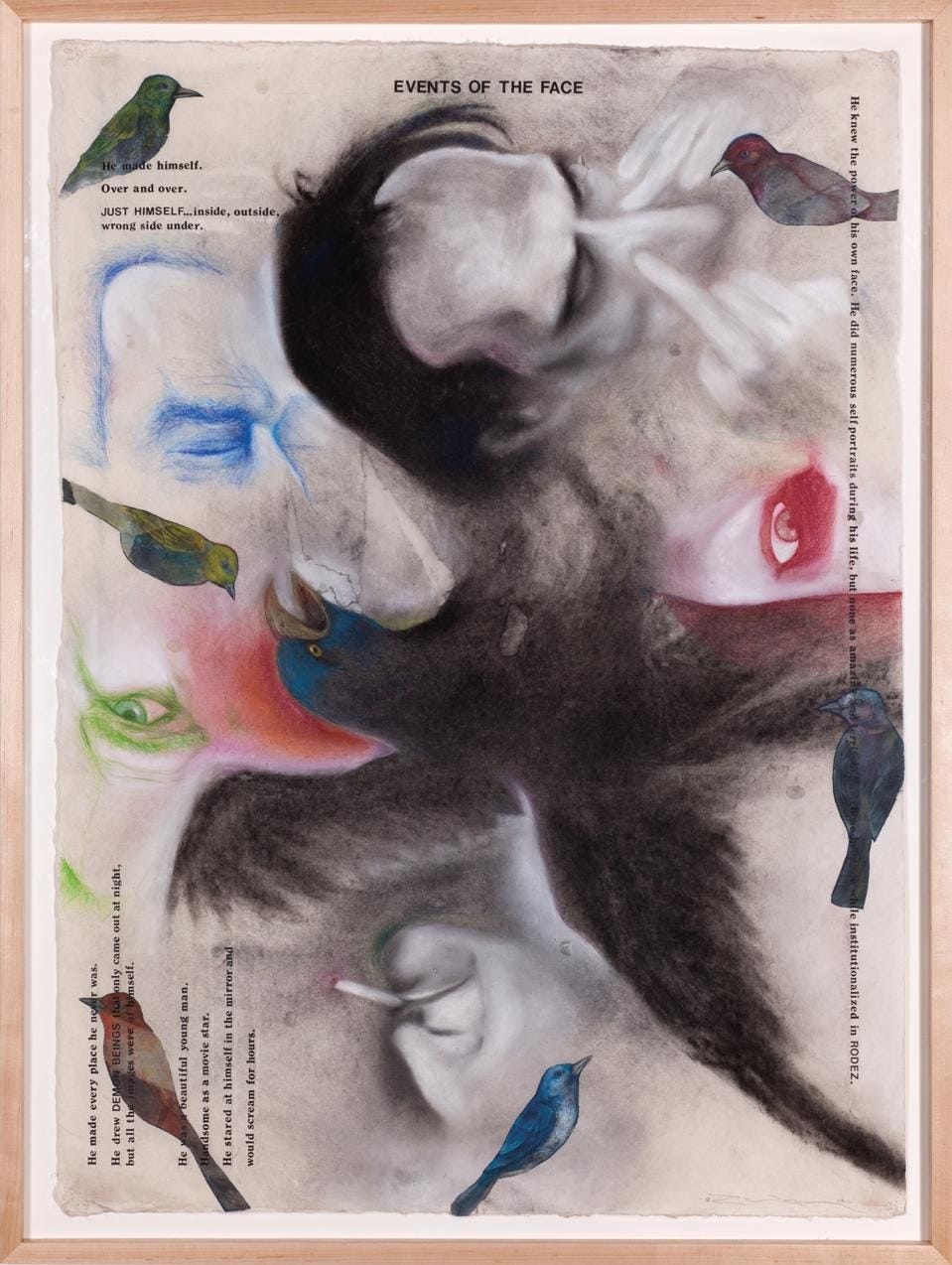

In 1975, he released his first album, Juarez. Juarez has a tale to tell that Allen can’t quit. “It returns to me,” he told me, explaining, “I did the first drawing here in LA and then when we went to Texas, that’s when I started: I wrote the first three songs and did the first group of drawings that went with it. And then it just kind of escalated….” Allen never had to choose between art and music. “I always just thought of ’em as the same thing. Both informed the other so much that it’s never been an issue.”

Over the years Juarez has manifested as an album, poetry, scripts, plays, performances, installations, and artworks. At its core is a story of two couples, one on the Texas side, one on the Mexican who cross paths to murderous consequences.

“I refer to it as kind of a haunting,” Allen said. “It was one of those things that I feel like I didn’t have that much control over it because those images were coming and the songs were coming, and it kind of built itself…. I just decided not to get in the way, just let it happen.”

Allen has recently published a book of the Juarez lyrics with 12 Etchings, available from the Nazraeli Press in several editions including a signed limited art edition.

With Juarez, in song and images, Allen felt that he had “sealed the deal.”

He was eager to make the next record. “We decided to form a record company… I was hoping to get Lowell George to produce it [and] Laurie Anderson to produce some of it in New York. Lowell was on the road, so I never even asked him. But at the last minute a friend called and told me Joe Ely [and his] band was in Lubbock.” Good musicians and a good studio was a compelling reason to record there. “And so, we just piled in and headed to Lubbock. And we recorded Lubbock on everything,

“The interesting thing was,” Allen now says, “I always spoke very lowly of Lubbock when I was out here in art school… I was totally negative about it. But then when I went back there and I met all these people that became lifelong friends, and who I played with, like Richard Bowden, Lloyd Maines, Don Caldwell… I cut this album, [ Lubbock On Everything] and we were listening to it, and [for the] first time it dawned on me of the great affection I had for Lubbock.”

Those first few albums, and those that followed, became beloved by other musicians. The artists who’ve covered Allen include Sturgill Simpson, Guy Clark, Little Feat, David Byrne, Doug Sahm, and Lucinda Williams.

LA Louver, Allen’s gallery, calls his characters “atmospheres.” Another multi-year, multimedia art project of several incarnations, is Ring Ring (LA Louver exhibited a small video sculpture from this series at Frieze LA). Ring uses the wrestling ring, in some ways the cathedral of his childhood dreams, as a metaphor for myriad game playing, In the words of the LA Louver press release, “In this work writing, gambling, and the wrestling ring… form the basis of a drama that ensnares the two characters who act out physical and psychological violence on one another brought on by intense passion and devious betrayal.” And that may be as good a reason as any to get out of town.

From Fresno, Allen moved to Sante Fe, which he admits was “a big change.” But, “Allen says, “We moved to Santa Fe because we found a really good place to live. And we both have studios, we have a house. It’s like a compound. We’ve always had an ideal of how we’d like to live.”

Over the years Santa Fe has changed a good deal. “It’s changed [but] it’s still pretty civilized.”

“Santa Fe’s still small enough that in 30, 40 minutes you can go any direction and be away from the human race in incredible country.” Allen said. “And it’s got amazing food…. But when we’re there, we lay pretty low, and I don’t do too many gigs there. It’s just where we work. “

In recent years, Brendon Greaves and Christopher Smith’s bespoke record label, Paradise of Bachelors has been re-releasing Allen’s oeuvre. As Allen explains. “Brendan dogged me for about eight years to re-release Juarez. I had it licensed to Sugar Hill. And then Sugar Hill sold out [and it] became Welk, and it got lost in the shuffle. But when my catalog came up (and the license expired), I called Brendan and I said, okay, let’s do it. And he did this fantastic package and wrote a beautiful essay for it. And that started a relationship.”

And the relationship continues “Lubbock came up [for renewal] and he did the same thing for Lubbock. And then we did all my radio shows. Pedal Steal, is the name of the record. I did four radio shows for NPR that had never been released. And then I did a dance soundtrack for Margaret Jenkins Dance company. So he reissued that.”

Amidst all these reissues, Allen was also approached about a biography. “Brendan had written so much in those records, that I just thought it was a natural for him to do it.”

Truckload of Art: The Life and Work of Terry Allen – An authorized biography by Brendan Greaves was published by Hachette on March 19. Allen told me, laughing, that “He says it’s an authorized biography. I don’t remember authorizing anything.”

Allen found the experience of having a biography written about him, strange. “I read the first couple of drafts. It’s odd reading [about your own life]. I used to give a problem in drawing class where I’d get students to look at a model on one side but draw the other side. Reading that biography, feels like that.”

Allen elaborated, saying that everything in the book is told one way, but that in life most things are actually several versions, at the same time. “Because that’s the way we all are,” he said.

Every event in his life, Allen told me, “is emotion to me. Making [art]work is some kind of emotion. Like music is emotion. Maybe that comes from listening to so many songs.”

Or put another way, “If you got the slightest bit of curiosity, you’ll find yourself somewhere else. Like that waitress at Denny’s [turning up] in Lubbock at the Fair, as the Gorilla Girl <laugh>. That’s the world.”