As Wallis Annenberg, of the Annenberg Foundation, said: “Helmut Newton is one of the most powerful and influential photographers of the past century — the place where art and fashion and subversion and aspiration all collide.”

Many years ago, on Jan. 23, 2004, to be precise, I was driving west on Sunset Boulevard when traffic stopped completely. There were police and an ambulance in front of the Chateau Marmont, where a car had crashed. I figured some celebrity-laden party had gotten out of hand, but later that night I learned that photographer Helmut Newton, the “King of Kink,” so-called for his shots of modern Valkyries posed like extras from Cavani’s “The Night Porter” or Sally Bowles’ co-workers at the Cabaret, had died, crashing his Cadillac into a wall across the street from the Chateau, the 83-year-old artist’s Los Angeles home base.

A retrospective of Newton’s work opens June 29 at the Annenberg Space for Photography, including his giant nudes, some featured in 8-by-8-foot prints made specifically for the exhibition. As Wallis Annenberg, CEO, president and chairman of the board of the Annenberg Foundation said in a statement accompanying the exhibition: “Helmut Newton is one of the most powerful and influential photographers of the past century — the place where art and fashion and subversion and aspiration all collide.”

He was also one of a handful of photographers who transformed fashion photography, and fashion advertising, into artworks, greater than the products they were selling (Irving Penn and Richard Avedon also come to mind). But even among this notable group, Newton’s work stood apart — both easily identifiable and much-imitated for the way he cast his models, often tall, blond and frequently naked, as either out-of-reach goddesses or playthings to be dominated and fetishized. Newton had a way of making both his subjects and his viewers complicit in the images’ sexual innuendo, or as Annenberg put it: “If Newton’s work was controversial, I believe it’s because he expressed the contradictions within all of us, and particularly within the women he photographed so beautifully: empowerment mixed with vulnerability, sensuality tempered by depravity.”

Given the exploration of power and debauchery within his work, it may come as little surprise to discover that Newton was born Helmut Neustadter in Berlin in 1920 to a prosperous Jewish family; his father owned a button factory. At 12, Newton purchased his first camera, and by 16 he was an apprentice to Yva (Elise Simon), a photographer who specialized in covering the German theater. If one is to believe Newton’s 2003 autobiography, “Helmut Newton” (Random House), the Nazis’ rise to power and the passage of the anti-Semitic Nuremberg Laws were merely an inconvenience to him, as Yva could no longer work (she would later be deported and murdered at Auschwitz), and because the beautiful blond girl he had a crush on rejected him. For his part, Newton went on to spend the rest of his life both idealizing Aryan blondes and making them submit to his will.

Helmut Newton

In 1938, following Kristallnacht, Newton’s father was briefly imprisoned in a concentration camp, forced to abandon the factory and flee with Newton’s mother to South America. Newton, then 18, could not get a visa and was sent instead to China. He made it as far as Singapore, where, according to his autobiography, he became a gigolo, or, at least the kept boyfriend of a much-older divorcee. From Singapore, he made his way to Australia in 1942, where he was interned by the British as a German national. Released to serve in the Australian army, at war’s end in 1945, he took Australian citizenship and changed his name to Newton.

After the war, Newton started a photo portraiture business in Melbourne where he met the actress June Brown, who would become his wife and partner. Newton spent the 1950s shooting for Australian and then British Vogue. In the 1960s, he moved to Paris to work for French Vogue. By the ’70s, his work was being featured in Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, as well as for Yves Saint Laurent.

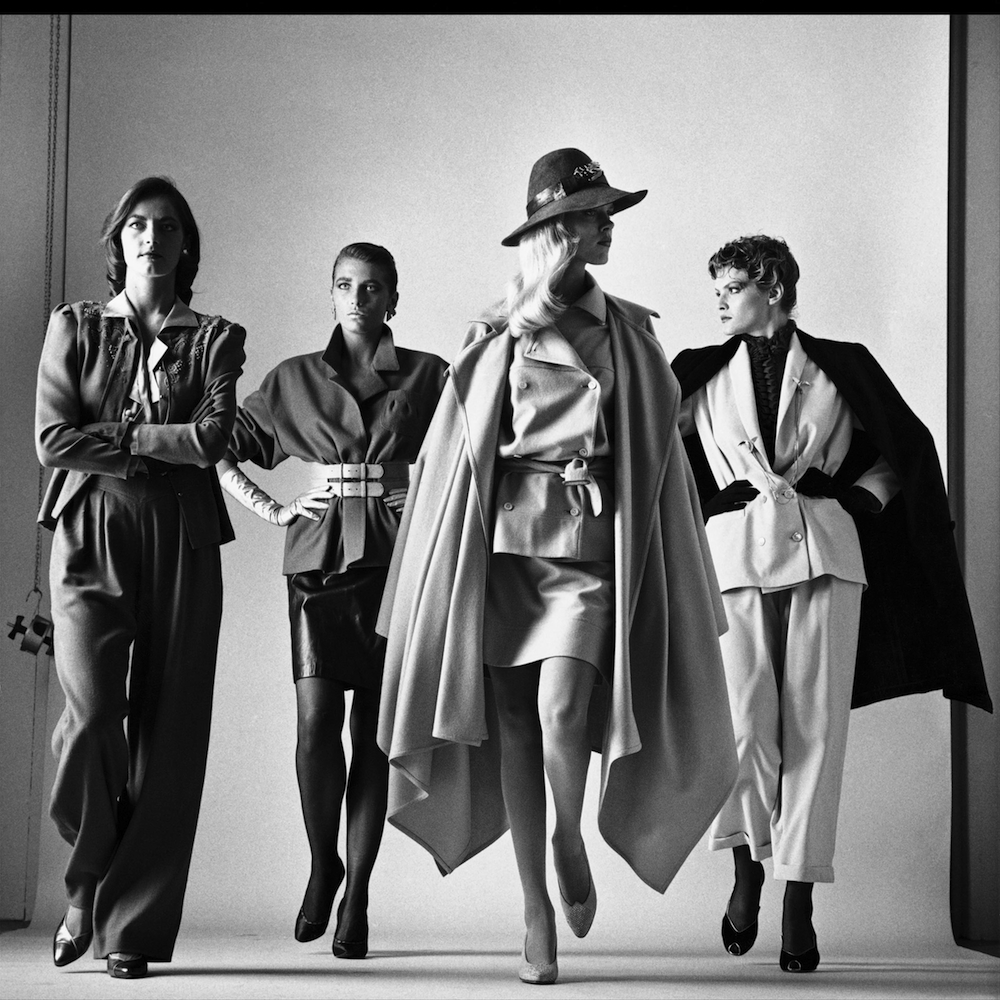

Yet no matter where he was, Newton brought a 1920s Berlin sensibility to his work. His images, always in black and white, explored fetishes not seen in polite culture — such as scantily clad models in leg casts or wearing orthopedic braces; or in leather corsets, with whips. In the Annenberg show, photos from this era show women dressed as men, women kissing women, women on all fours wearing a saddle, women in garters, in high heels and stilettos and not much else — images meant to provoke, to incite and, most important, to hold one’s attention, as if giving us a peephole view into an unfolding narrative.

In addition to the more than 100 prints featured in the show, the Annenberg will also screen two films about the artist, both showing continuously in the galleries: “Helmut by June,” was directed by June Newton, wife of 56 years (also a professional photographer, working under the name Alice Springs), and in the film she goes behind the scenes at photo shoots and in their homes to discuss his work and their private life over the years. Also showing will be an original documentary commissioned by the Annenberg from Arclight Productions, including interviews with Newton’s models, stylists and fashion editors, as well as his assistants and friends.

After Newton’s death, fellow German fashion icon Karl Lagerfeld told The New York Times: “Berlin was him, he was Berlin. … He was a graphic artist with a sense of composition in his imagery, with Berlin’s silent movies and a whole history in his pictures. … He was the last artist who had that Jewish wit, the last link to a Germany that I did not know but that I can understand.” A Germany that was murdered out of existence, that Newton really didn’t know either — not the Jewish part — and whose decadence he could only observe, as a young apprentice, staring through a lens, wanting in.

“Rue Aubriot, Paris Collections,” from the series “White Women,” 1975. © Estate of Helmut Newton

“Helmut Newton: White Women…Sleepless Nights…Big Nudes” | June 29-Sept. 8, 2013 | The Annenberg Space for Photography

2000 Avenue of the Stars | Los Angeles, CA 90067 | Tel: 213.403.3000 | info@annenbergspaceforphotography.org | annenbergspaceforphotography.org